Why are national solutions to the COVID-19 pandemic so different? And what makes some approaches more successful than others? National and regional cultural differences are key factors that are often overlooked.

By looking through four key national and regional cultural lenses, we can gain new insights into why countries are fighting the pandemic differently and perhaps why some countries are succeeding more quickly than others.

The four intercultural frameworks below have been developed and expanded upon by globally renowned intercultural researchers such as John Condon and Fathi Yousef, William Gudykunst and Stella Ting-Toomey, Geert Hofstede, Young-Jun Kim, Clide Kluckhohn and Fred Strotbeck, Junko Tanaka Matsumi and Fons von Tromepenaars, among others.

1) Power Distance (PDI)

- Ask: Is the culture egalitarian or hierarchical? What is a culture’s attitude to authority?

2) Masculinity* (MAS)

- Analyze: Do we (as a group, a culture, a country) value assertiveness, competition and winning or contentment and quality of life?

* This continuum does not refer to gender.

3) Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI)

- Question: How comfortable are you with the unknown? How carefully do we assess risk before we act?

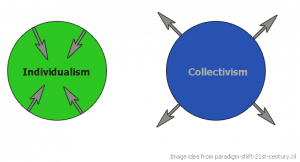

4) Individualism (IDV)

- Reflect: Does the culture believe that its strength and national rights reside within the individual or does the culture believe its success stems from its collectivism and interdependency?

More than a half-century of research confirms that these key national and regional cultural differences are often unspoken and thus unconsciously held. They usually stem from common core values, assumptions and behavioral expectations.

When in crisis or under stress, the group norm within a culture will often default to these national rules to solve problems and get things done. As renowned Dutch interculturalist Geert Hofstede once said,

“National culture cannot be changed, but you should understand and respect it.”

And, as with any cultural framework, it’s critical to remember that these four cultural continuums of behavior reflect norms for a group. Within that group, they represent the median, and thus don’t apply to all individuals within a group, region or nation.

Let’s take a look at just one of these four key cultural differences more closely.

- Did you know that every major intercultural study finds that the U.S. is the most individualistic culture in the world?

- Yet nearly two-thirds of the world’s cultures identify as collectivist or group-oriented.

When we look through the lens of individualistic versus group-oriented cultures, perhaps it makes sense that in collectivist countries like China, Singapore and South Korea, citizens accepted COVID-19 national testing, mobile tracking tools such as TraceTogether, daily temperature checks and country-wide shutdowns for the good of the nation. In some Chinese cities, individuals who did not wear masks or otherwise strayed from stringent national shut-down rules were publicly shamed, bullied and even reported to authorities by citizen groups.

Meanwhile, in more individualistic countries like Germany and the United States, each state or region initially created its own plan to address the COVID-19 virus. When some German youth were found to be holding “Corona parties,” the government had to explicitly state that no more than two Germans would be allowed to gather at a time. Markus Blume, general secretary of Chancellor Angela Kerkel’s ruling Christian Democratic Union tweeted, “stay at home, otherwise curfews are inevitable, adding the hashtag #staythef****athome.”

Meanwhile, in a more patchwork approach, individual U.S. states each have their own pandemic solutions, and two states have yet to declare an official state of emergency. Some states are openly competing with each other for federal assistance and supplies. In Missouri, Governor Mike Parson said he was not likely to make a state pandemic policy, adding, “It’s going to come down to individual responsibilities.” And we can still observe our U.S. neighbors attending church services or sunning on southern beaches with hundreds of others, despite state-wide bans.

Of course, differing political systems also play a factor in national pandemic strategies and compliance. But that doesn’t explain everything. Although China is an autocracy, India is not. And yet just last week, India shut down the entire country with only four hours ‘ notice—which meant voluntary cooperation from 1.3 billion people to stay home.

Although these four intercultural lenses help explain how nations react differently to and solve problems in a crisis like COVID-19, we can also see regional differences at play.

In the U.S. state of Oklahoma, Kevin Stitt declared a state of emergency because of the COVID-19 epidemic– but with an important asterisk.

His Chief of Communications then shared that, in addition to using common sense and following health precautions, Oklahomans should “live your life and support local businesses. The governor will continue to take his family out to dinner and to the grocery store without living in fear and encourages Oklahomans to do the same.”

State-wide pandemic plans and messaging demonstrate how individual rights and freedom (two core U.S. American values) can conflict with state and national public health orders.

As you absorb COVID-19 pandemic news around the world, take a moment to view the diverse international response through these four cultural lenses.

By using a more culturally competent approach, perhaps we can create and position COVID-19 solutions that will be more quickly accepted and thus work more effectively within countries and worldwide.

Written by: Mary Beth Lamb and Dr. Amy Tolbert

Works Cited

Budryk, Zack. “Oklahoma Governor Will Continue to ‘Take His Family out to Dinner’ amid Pandemic.” The Hill, 16 Mar. 2020, thehill.com/homenews/state-watch/487846-oklahoma-governor-will-continue-to-take-his-family-out-to-dinner-amid?fbclid=IwAR3rxAziRMGWFeQpqr-RStandly-GJEfBZRXOMaiV4VUDF5RC0h4G9Dw0ro-N2_HsKo.

Casey, Ruairi. “Germany: Will Authorities Crack Down on ‘Corona Parties’?”, Aljazzera News, 19 March, 2020.

Condon, John & Yousef, Fathi (1977). An introduction to intercultural communication. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrul Educational Publishing.

Gudykunst, William & Ting-Toomey, Stella (1988). Culture and interpersonal communication. London: Sage.

Hofstede, Geert (2001). Culture’s Consequence London: Sage.

“Compare Countries.” Hofstede Insights, www.hofstede-insights.com/product/compare-countries/.

Kim, Young-Yun (1992). Intercultural communication competence: A systems-theoretic view. In William Gudykunst & Young-Yun Kim (Eds.), Readings on communicating with strangers. An approach to intercultural communication (pp.371-381). New York: McGraw Hill.

Kluckhohn, Clide & Strodtbeck, Fred (1961). Variations in value orientations. Evanston: Row Peterson.

Stanley, Becker & Janes, Chelsea. “As Virus takes Hold, Resistance to Stay-at-Home Orders Remains Widespread,” The Washington Post, 2 April, 2020.

Tanaka-Matsumi, Junko (2001). Abnormal psychology and culture. In David Matsumoto (Ed.), The handbook of culture and psychology (pp.265-286). New York: Oxford University Press.